Although flavonoids and bioflavonoids have long been incorporated into the care plans of many, individuals may be unaware of the role they play. The following are a few clarifications for what these plant powerhouses are, where they came from and how to investigate them, and suggestions during recommendations.

Flavonoids and Bioflavonoids: Plant Powerhouses

Flavonoids are characterized as a plant pigment that is found in many fruits and flowers. The name 'flavonoid'; which has the Latin stem, 'flavus' means yellow. The common colors for these particular pigments are red, yellow, blue, and purple. The pigments are found in the cytoplasm and plastids of flowering plants. As opposed to other pigments such as chlorophylls, carotenoids, or betalains, certain flavonoids play a distinct role in fruit ripening and capturing certain variants of light within the UV spectrum. They seem to be highly prevalent in plants from the citrus family, as well as pigments common in tea, red wine, dark chocolate, and richly-colored berries.1

Bioflavonoids are polyphenolic compounds found in plants. There are over 5,000 bioflavonoids identified throughout the plant kingdom, many of which have been the subject of preclinical and human research.2 Bioflavonoids have been widely recognized to affect a wide range of systems in the body.

A History and How to Investigate

Individuals are encouraged to understand the plant sources of these compounds for dietary management, as well as the use of dietary supplements containing these ingredients. In order to fully utilize these compounds, it is important to note and differentiate the various terms used throughout the supplement industry, within peer-to-peer conversation, and searchable terminology utilized during research studies.

The use of the terms flavonoid and bioflavonoid are essentially interchangeable. Historically, bioflavonoids or flavonoids were called vitamin P. You will often see the term vitamin P in early studies before the 1980's. There are numerous classes of flavonoids including isoflavones, anthocyanins, flavanones, flavonols, to name a few.3

While investigating applicability of flavonoids within a care plan, bear in mind these classes and utilize their name variants when attempting to compile a comprehensive list of available literature. Four types of flavonoids have been researched for clinical use. These include: polyphenols derived from tea, quercetin and its diverse molecular cousins, citrus bioflavonoids, and proanthocyanidins found in grapes and certain pine species.4 These four types are often broadly categorized in abstracts of research articles.

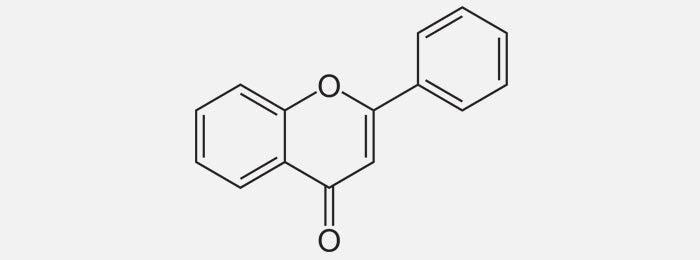

From a biochemical prospective, flavonoids are characterized by a hetercyclic oxygen ring. This unique aspect of their make-up can help to identify and differentiate a flavonoid from other pigments in the animal kingdom. Depending on the group of flavonoid, there may be various constituents attached to this hetercyclic oxygen ring.5 For example, flavonoids in the subclass quercetin have a similar structure and certain conventional therapeutics. Its mechanisms can be investigated with this in mind.5 Identifying the various constituents attached to a heterocyclic oxygen ring can aid in identification of which class of flavonoid the food, herb, or active ingredient belongs to as well.

Recommending Bioflavonoids

When recommending a bioflavonoid or complex of bioflavonoids as part of a comprehensive plan, practitioners should attend to the concerns of bioavailability. Many bioflavonoids are less bioavailable as the dose increases. Therapeutic dosing of bioflavonoids is often paired with technology that enhances bioavailability. For example, quercetin has a low bioavailability. Research shows oral administration of quercetin results in a low absorption and utilization, and when given via IV administration, it metabolizes within a few hours.5

Two ways supplement manufactures are addressing the issues of bioavailability and absorption are by creating delivery of bioflavonoids in a water-soluble form, which can reach the blood stream more effectively, or in a lipid soluble form for a slower, but effective rate of absorption. Without a proper delivery method, absorption has been shown to be very low. Many common bioflavonoids (such as those containing vitamin C) are water-soluble and perform best in formulas that allow for proper delivery.

It should be noted that microorganisms in the gut degrade flavonoids. Balancing gut flora is recommended to optimize utilization of bioflavonoid compounds. Healthy digestion plays a key role in the ability of the body to absorb flavonoids effectively. Bioflavonoids are best taken on a full-stomach, and when done so will aid in obtaining an increased amount of absorption.6 When determining clinical applicability in research, take note of the form used within the research studies to evaluate the effective form needed to deliver the appropriate type of bioflavonoid.

While the surface of the topic of flavonoids and bioflavonoids has barely been scratched, it has also been said that brevity is the soul of wit. With the above in mind, there is certainly a place for a deeper understanding of what flavonoids are, how they function within the body and how to properly identify, investigate, and integrate them within clinical practice.

REFERENCES

- Plants: Causes of Color. http://www.webexhibits.org. http://www.webexhibits.org/causesofcolor/7h.html.

- Narayana, K. R. et al. Indian journal of pharmacology, 2001;33(1): 2-16.

- Schwinn KE et al. Annual Plant Reviews, Volume 14. Oxford, U.K. :Blackwell Publishing; 2004: 92–149.

- Formica, J.V et al. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1995;33(12):1061-80.

- Gaby, AR. Nutritional Medicine. 1st ed. Concord, NH: Fitz Perlberg Publishing; 2011:214-217.

- Hollman, PC. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2004; 42(sup1): 74-83.